He dug his heels into the dirt, bat over his shoulder, eyes burning into the ball before it even left my hand. He had a deeply intense look on his face—it’s the same look he gets when he’s absorbed in a math problem or a box of Legos, or like the time he sat on the kitchen floor one marathon morning figuring out how to tie his shoes. I pitched the ball and watched his eyes follow it. There was a moment’s hesitation as he looked for that perfect split second of truth. He swung.

Crack!

That “soft hit” training baseball sailed over my head and practically took out a window twenty feet away.

“What a hit, Tyler! That’s the way you do it!” I whooped. I ran to our makeshift home plate for a congratulatory high five.

He grinned and smacked both hands instead, ten times in a row (a practice he dubs his “high one hundred”). Then he looked up at me and said, “Can I go in and finish my Legos now?”

As far as baseball’s concerned, the boy’s got it. Problem is, he doesn’t want it.

At the start of first grade, his after-school ritual has been the same. He gets off the bus. He has a fruit or a vegetable to compensate for the Fluffernutters and Pop-Tarts he ate for lunch. I kick him outside. He promptly begs to come back in. “Come on,” I coax. “Let’s go throw a few balls around in the backyard.” He quietly acquiesces.

“Don’t you like baseball?” I interrogated one time when he tired after the first dozen pitches.

“It’s OK,” he shrugged.

“Well, you should like it,” I said. “You’re good at it. Wouldn’t you like to be a professional baseball player someday?”

“No,” was his resolute response. “I want to be a UPS driver.”

“A UPS driver?” The stadium in my head grew silent. When most boys pick a future career, it usually requires a uniform—whether it be an athlete’s, soldier’s, police officer’s, fire fighter’s or other such heroic figure. Head to toe in brown with a “United Parcel Service” patch doesn’t usually fit the bill.

“They get to deliver people really cool packages,” he explained. “Everyone’s always happy to see the UPS guy.”

“There’s nothing wrong with being a UPS driver,” I said decidedly. “But you need a safety net. Let’s keep practicing baseball. You know, just in case the UPS thing doesn’t work out.”

You may call me a dream squelcher. And I think at the time I knew I was. But for the longest time, I didn’t know why.

They say as parents we subconsciously dream up for our kids what we couldn’t accomplish for ourselves. When I was a kid, there was a field of dreams in my head bigger than Ray Kinsella’s cornfield. And much of it was because of a girl named Trang Bentley.

Trang was a twelve-year-old Vietnamese girl who played on the Tigers, the team my dad coached for Little League baseball. With eleven boys on her team, she didn’t stick out simply because she was a girl. She batted fourth on the lineup because of her hard, clean line drives. She could block a rocket for crossing her path at shortstop, and she fired the ball to first base with pinpoint accuracy. I still remember the way my dad would come home, exhilarated after a win, raving about his star player.

“Trang smacked another one over the fence,” he gushed that last year he coached the majors. It was the same year the Tigers made it to the league’s World Series—a string of victories he attributed largely to Trang.

I saw that look in his eye, I heard the pride in his voice, and I had only one wish. I wanted to be the girl that made my father look and talk like that. I wanted to be Trang.

My dad was one of four boys growing up. He had a sister, but she died of a hole in her heart when she was only four months old. What did he know about girls? I decided he’d been ripped off, and that he was somehow incomplete without a son. And I was determined to fill that void.

Of course, I could never be Trang Bentley. I could hit and catch a ball, but I wasn’t a natural like she was. I started playing catcher for softball when I was old enough to join a team. But when I didn’t make varsity softball junior year of high school, that dream was over.

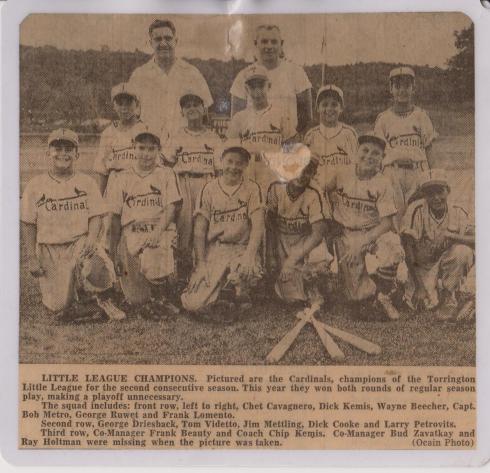

My dad (top center) and the Tigers, Torrington Little League, 1983

Early this fall my dad and I loaded up my trunk with bats and balls and took Tyler and his sister to the field at East School in Torrington, my elementary school alma mater. There is no greater full-circle moment than taking your child to play ball in the same field you played on as a kid. I crouched behind home plate while my dad pitched. Seeing him standing on that pitcher’s mound, my mind rewound itself back thirty years—and suddenly I was holding that bat, and he was standing there with a full head of jet black hair and half smile on his face as he threw the ball over the plate.

“Square off. Choke up a little,” he instructed Tyler—the same instructions I’d heard so many times. The déjà vu came to me in tidal waves.

Except for one part.

Smack!

Crack!

Whack!

One by one, Tyler hit the ball, whether the pitch be high, low, inside or out. My dad’s half smile grew as wide as a bat is long. “Do you ever miss?” he teased.

Tyler grinned back at him. And at that moment, I realized how much he’s like his grandpa. Both are tall, lanky, and wiry in their build. Back in my dad’s day, he was the skinny kid that no one in their right mind wanted to mess with. Tyler’s like that. At forty-seven pounds, he can hoist a twenty-pound dumbbell over his head and hold it there. He can zip back and forth across the monkey bars and never get tired, skipping every other bar along the way. At that moment, he knew he had his grandfather’s complete attention and approval. He was basking in the glow of Grandpa’s glory.

Until it was his sister’s turn, that is.

“Eva’s up!” I yelled from behind the plate. “Tyler, go on out and field the balls.”

He lay down his bat and sighed. “I’m tired,” he whined. “Can we go back to Grandma and Grandpa’s now? I want to finish my puzzle.”

I stared at him.

It brought me back to the JV softball field at Torrington High School, freshman year. I had just smacked a ball into the outfield during practice. Leisurely, I walked to first base.

“Hustle!” Coach Marshand yelled from the sidelines. “What are you doing out there, Petrovits? Taking a nature walk?”

But I didn’t listen. I knew I’d hit it far enough that I didn’t have to hurry. And besides, I wanted to be cool. And quite simply, it wasn’t cool to hustle.

I was an underachiever all through school. Even as an adult, I walk methodically through life, dreaming up all the things I plan to accomplish, but never quite cut through the day-to-day grind fast enough to get to item #1 on the Big List.

And suddenly, I looked at Tyler and recognized what I felt as fear. In that regard, I didn’t want him to be anything like me.

“What do you mean, you want to finish a puzzle?” I rebuked. “This could be the last sunny day of the whole year—and you want to work on a puzzle?! We drove all the way here, and we’re going to have thirty freaking minutes of fun. Now get out there in the field—” and before I could stop myself, I added, “Hustle!”

He hustled all right. Right over to the bottom of the stairs at the sidelines. He flung his bat aside, sat down and cried.

For a second, I was Tom Hanks, right after Bitty Schram burst into tears after blowing a two-run lead. Nearly seventy years after World War II was over, there’s still no crying in baseball.

Soon enough, I realized what I was feeling wasn’t anger or disappointment or disgust after all. It was still fear, but one that had nothing to do with me at all.

Tyler is on the autistic spectrum. When he has to talk to people, he freezes. As a parent, it has become a routine to watch children make one-sided attempts at conversation with him, then turn to me and ask, “Why won’t he answer me?”

“Please keep trying.” I try not to beg. “He just needs a lot of time to warm up to you.”

But heartbreakingly, kids Tyler’s age just don’t have that kind of time. Or at least, they don’t have the perseverance.

When Tyler was three, just before self-consciousness set in, he found one boy, Shane, who didn’t seem to mind his quirkiness. When the two of them are together, they wreak havoc, tearing through the house, screaming and laughing so hard I can barely hear myself speak, scaring the cats and fooling around at the table. It drives Shane’s parents crazy. But as for me, I’m just happy to see my boy acting like a normal kid.

For a seven-year-old boy, Shane is a model athlete. He is husky, coordinated, and the image of a professional football player in the making. At soccer practice, the coaches pull him in the center for demonstrations. Parents flock his parents after games to sing his praises.

It makes me wonder, as the boys get older, when their interests diverge and Shane starts bonding with his future teammates, if he’ll continue to make room in his circle for the quirky boy who speaks to no one but him. I can’t even bear to think about it.

As for Tyler, he’s good at math. And building stuff. If I ever need to put something together, like a set of shelves or a shoe organizer or any other annoying gadget that comes in a box and requires assembly, he’s all over it, like it’s a great big puzzle. If I need to use some complicated household gadget, like the juicer that I have no idea how to put together, I call on him. If something needs fixing, he’s my man. Unfortunately, so obsessed is he with building and fixing that he often takes things apart, like pens and calculators and watches, and can’t figure out how to put them back together. But even as I scoop up the loose parts and toss them in the garbage, I can’t fault him for his curiosity.

Last year he announced that he could count all the way to 10,000. And he did—he sat there perched on our kitchen counter, started at one, and methodically forged right through his first thousand. Each time I reentered the kitchen, I heard him chanting. “Seven thousand three hundred ninety-eight, seven thousand three hundred ninety-niiiiiiiine…seven thousand four hundred! Seven thousand four hundred one…” The whole time, he was pushing a set of base 10 blocks around, modeling each number.

“Tyler, don’t you think it’s time to give it a rest?” I pleaded. “You’ve been at this all morning. It’s a beautiful day. Why don’t you go outside with your sisters on the swings?”

“…seven thousand four hundred eleven…” he was oblivious, tunnel-visioned, and on a mission. Part of his disorder means that he must go through the hours of senseless ritual and repetition, and if he doesn’t, he will never overcome the feeling that there is a piece of the universe left incomplete. And so, I bit my lip and allowed him to sit there on the counter plugging away until he reached that final digit.

When he finished, he looked at me like it was the first time he noticed my presence all morning, pride all over his face, and announced, “Did you hear that? I just counted to TEN THOUSAND!”

“I did,” I replied with a smile. We high-one hundreded, I messed up his hair, and he jumped down from the counter to join his sisters. And as I scooped up all his base 10 blocks, there was only one thought in my head that I couldn’t shake: someday, my boy is going to get his ass kicked.

It’s horrible, I know. As parents, we’re supposed to want our kids to be exactly who they are. But I am dying for my kid to just do normal, first-grade things. I want him to collect baseball cards, put frogs in his sisters’ pockets, hit a ball through a window. I want him to bring his friends home from school and beg me to let them stay for dinner. Just once, I want to get a call from his teacher telling me he was fooling around in class.

Maybe I was being somewhat hysterical when I went to Dick’s Sporting Goods and purchased a junior bat, mitt, batting gloves, bag of balls, catcher’s mask and “Future All Star” baseball cap. But I thought it would add a spark of enthusiasm to our practice.

After school this week, Tyler was reluctantly practicing his swing in the waning October sun. “You see, you put all your weight on this leg.” I patted his right leg. “Bend you knee a little and point it that way. That’s right. Now when you swing, all your weight goes over to this leg.” I patted his left leg. “Swing all the way around, so the bat lands on your left shoulder. That’s it. Perfect!”

“Are you sure you’re teaching him right?”

I looked up and saw Doug, standing over the deck, watching.

“Yeah, I’m sure,” I shot back. “What do you know about swinging a bat?”

“Why don’t you just let him swing it the way he wants to?” he shrugged.

“Don’t you have a bunker to prep?” was my wry response.

I was irritated, to say the least. I knew going into our marriage that a sportsman, Doug was not. Growing up, while his peers were getting involved in extra-curricular activities after school, he was wrapped up in the wrong kind of extra-curricular activities of his own. As an adult, extensive training in the military and police academy turned him onto target shooting and as time went on, bow hunting. I think the debate over whether hunting qualifies as an actual sport will always be a contentious point in our marriage.

As our boy gets older, I find myself getting more and more resentful that he’ll never have a father figure to turn him onto sports. A boy doesn’t get excited throwing balls around the yard with his mother the way he would with his father. What was I doing his job for, anyway?

“When he’s old enough, I’ll take him out shooting,” Doug vowed the last time I complained about it. “He’ll be good at it, cause he’s patient and persistent, and he’ll have a steady hand. He’ll love it!”

“It doesn’t matter,” I countered. “Being a good shooter isn’t going to keep him from being the last one picked at recess. There’s no after school bow hunting league he can play on after school. Boys don’t get called wimps because they can’t shoot a bull’s eye on a target. He needs to learn baseball, soccer, basketball, hockey. He needs to be able to hold his own on a playfield. Things normal kids his age can play!”

It’s hard to debate a father’s role in a kid’s love of sports. Some of my best memories as a kid were watching the Mets with my dad. Whenever we watched a game together, the whole world stopped around us. The only time he let me stay up past my bedtime on a school night was to watch the final stretch of a game, no matter how long they went into overtime. Having a favorite team with a parent is a bonding experience that’s hard to match with anything else.

He was bringing me up the only way he knew how. Just before he went off to the army, his own father slumped in his car after a night of bowling and died of a heart attack, so their time together was cut short. He was a stern man who loved to drink and never showed his boys a hint of affection. But the one thing they had in common was baseball.

The five of them—my dad, his father and three brothers—were diehard fans of the Brooklyn Dodgers, who broke their hearts and moved to Los Angeles when my dad was at the tender age of eleven. For four long years in their Torrington home, baseball was gone but not forgotten. All the boys on Elmwood Terrace came together after school to play baseball in the street, resurrecting ghosts of the heroes who abandoned them. Television didn’t work well back then, and as the family hated the Yankees (a team they deemed managed by rich people who bought off all the good players from other teams), there was no one within driving distance to fill the void.

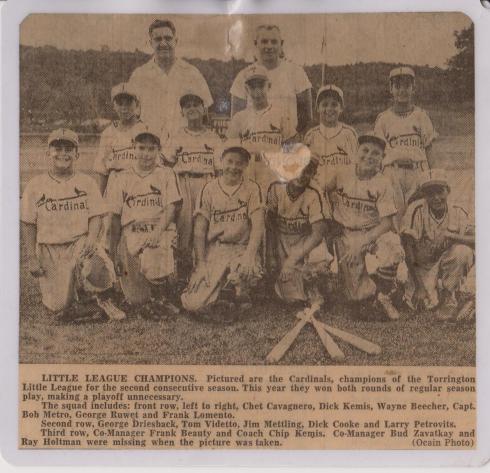

My father, 1957, when he played for the Cardinals in the Torrington Little League.

That is, until 1962, when the Mets made their glorious debut at the Polo Grounds, and the baseball craze was reignited between my dad, his father and brothers. It was a tradition my father was determined to carry on in his own house—even if it was a house with a wife and two girls.

In 1964 the Mets found a home at Shea Stadium, and by the time I sat in it twenty years later, it was the stuff dreams were made of. If I close my eyes, I can still hear the clamor of fans jumping to their feet with every ball smacked in the outfield, the organ music, the feet-stomping exhilaration culminating with that familiar da da da da da da…CHARGE! I remember my sister reading a magazine and the twirling of my mom’s knitting needles. (That’s right. Whenever my dad dragged my mom to the ballpark, she knitted sweaters.) My dad and I shared a oneness with the crowd—I was dazzled by the way a stadium full of fans sang, chanted, booed and cheered on cue; how they synchronized like a coliseum of cows every time Mookie Wilson stepped up to the plate; how they could wordlessly orchestrate a wave from one end of the stadium to the other. I remember how hard my dad and I laughed at the crazed extremeness of the fans, right down to the topless fat guy with the booming voice and orange and blue body paint sitting behind us. “C’mon, Darryl! Hit me a homerun, and I’ll buy you a hot dog!”

Those days were gone when the teen years set in. By that point, it occurred to me that baseball was all my father ever talked about to me. “Mets are three games out of first,” he’d announce upon coming home from work, without even bothering to ask me about my bad hair day or whether my crush of the week talked to me at school. I decided he was trying to turn me into the son he never had, and I resented it.

I made a clean break of it one day and decided I wasn’t going to watch any more games with my dad. A few times he asked me about it, but eventually he stopped saying anything at all. Late at night, I’d get up and watch him sitting in his easy chair, quietly watching the Mets by himself.

Today I look at my father, and I know that I had him all wrong. He didn’t care if I liked the same things he did, and he was proud of me no matter who I wanted to be. Even after his third daughter was born two years after the Mets won their second and last World Series in ’86, he was thrilled to have yet one more girl. He wasn’t using me to fill a void, and he wasn’t trying to make me into someone I wasn’t. I was his daughter, whether I was going to watch the game with him or not.

It wasn’t that my dad didn’t know anything about raising girls. It was that in all my teenage stupidity, I didn’t know a thing about being a parent.

My father is old now. His once jet black hair is now wispy and gray, and he’s got that wise old man look about his face when he stoops down to talk to his grandchildren. People always say, spend time with the ones you love while you still have time. But the truth is, once you have children of your own, that time is for the most part up.

It’s human nature to want to make up for your parenting shortfalls through your grandchildren, and I’m pretty sure as I watched him toss those baseballs to Tyler at the East School field that he felt he was getting a second chance. And maybe, as I’ve been pitching those balls over our makeshift home plate, I’ve been clinging to a second chance with my father.

Today I watched Tyler sitting at his Lego table, analyzing the instructions, popping each piece in place. After a while his concentration was broken, and he looked up and caught me watching him.

“Mom, come check this out,” he said. Before him was a spaceship, and he flipped it upside down and pressed a lever. Out popped a little ship.

“That’s really cool,” I said. “You made that all by yourself?”

I caught a glimpse out the window behind him and saw a smattering of baseballs, a bat, glove and empty basket strewn across the lawn. The skies were getting gray, and I figured I should gather everything before it started to rain.

I scooped everything into the basket and propped it in a corner of the garage. I stared at it for a moment. And as I stared, the clamor from Shea Stadium that had been resonating in my ears grew dim. The players in my head evaporated from the field, and one by one, every last fan was gone.

But it didn’t stay empty for long.

In my mind, a UPS truck came tearing through the stadium. A tall, lanky man with a wiry build burst out and erected a skyscraper right there in center field. It was ten thousand stories high, to be exact.

I had a decision to make. I could pick up a bat and try to knock down his foundation. Or, I could open the door, take his hand and climb all 10,000 floors with him.

Something tells me to put down that bat and start climbing. Because in the end, my boy will choose his own destiny.